Venus

Vessel Name: Venus

Henry (Harry) James Ball

Charles Aslesen

Lost At Sea; Bodies never recovered

21 August 1923

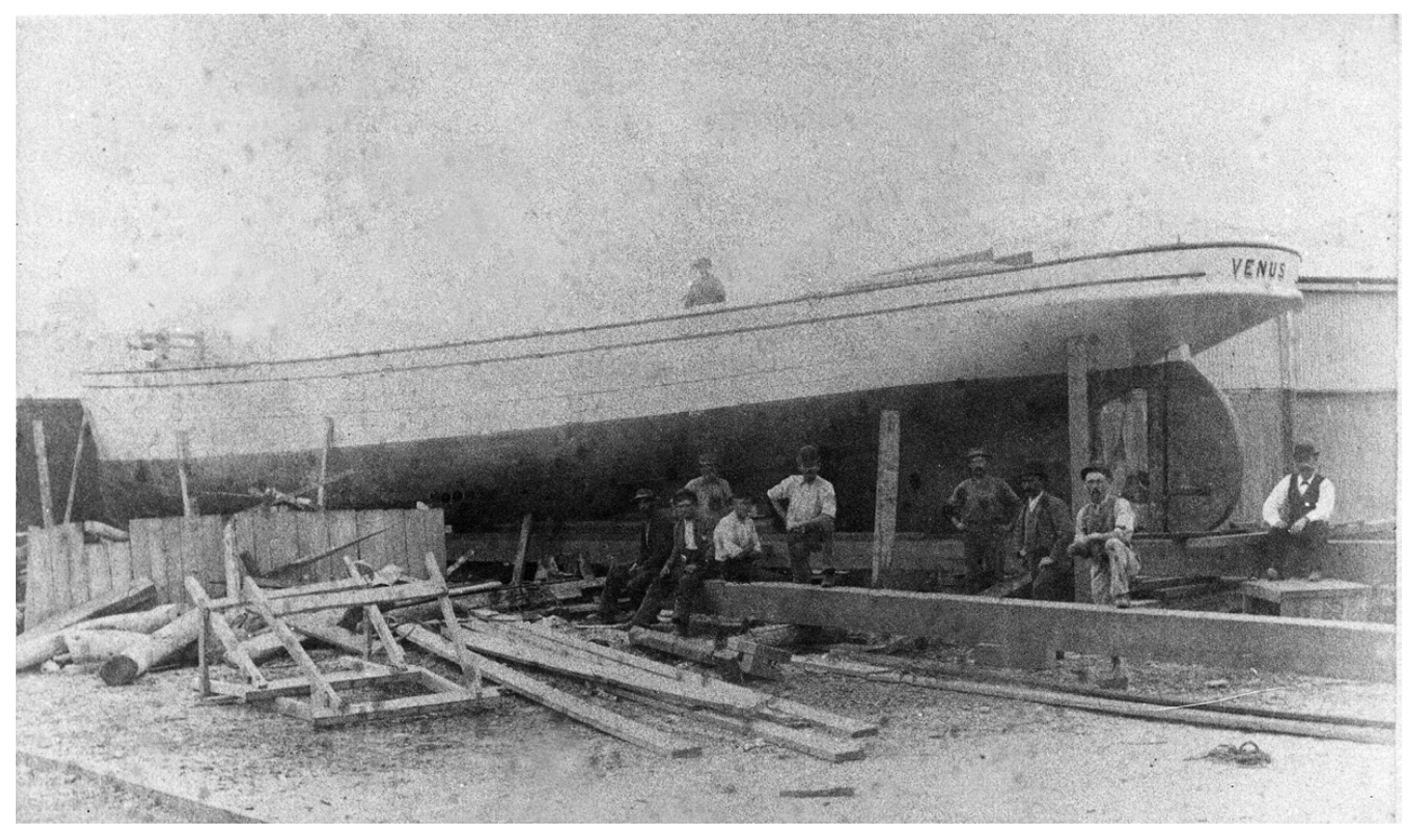

The S.S. Venus was a 62-ton, single screw steamer built in Fremantle in 1897 by Robert Howson. The Venus was carvel built with a straight stem and counter stern. The engine was a two-cylinder compound steam engine, producing 15 NHP, or 45 IHP, giving a speed of eight knots. There was one steel boiler operating at 120 pounds-per-square-inch pressure.

The Venus being built in 1897, Photo Fremantle City Library

James Ball on LEFT at daughters wedding

James Ball headstone

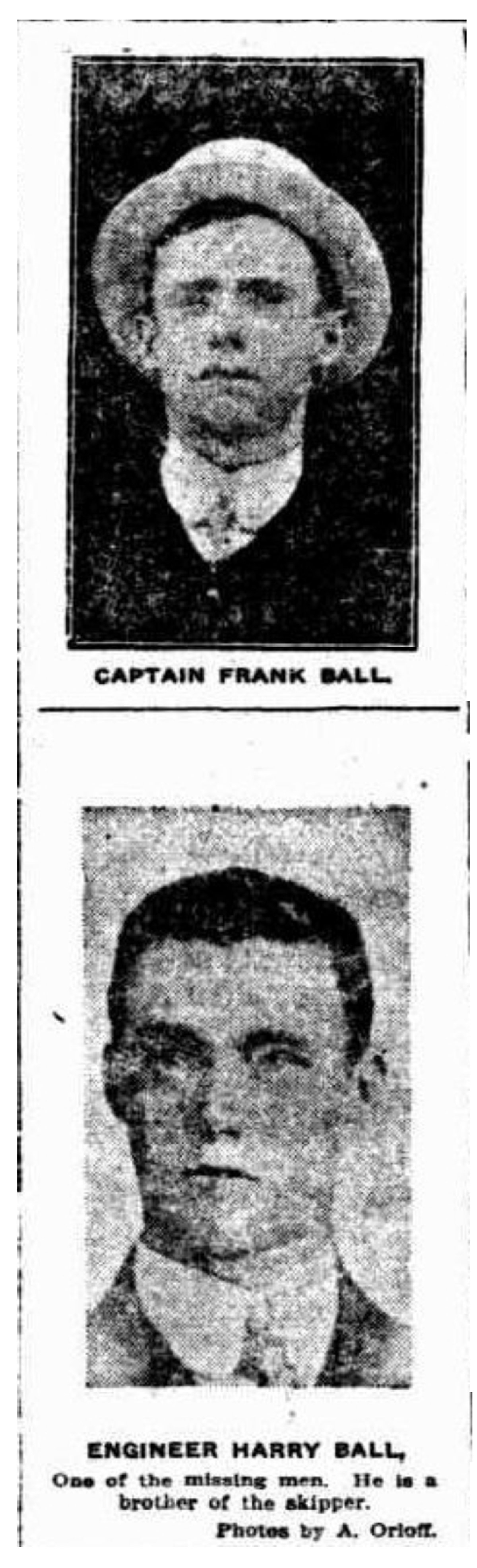

The Ball Brothers Portrait published in the Sunday Times

The vessel had auxiliary sails and was described as a “steam-sailer”. The Venus was originally built for the Venus Steamship Company Limited of Fremantle and was later sold to William Bower Fallowfied, a guano merchant of Geraldton in 1908. He in turn sold it to the Western Australian Government in 1909. In 1919 it was sold to a family consortium consisting of Master-Owner, Captain James Mathias Ball (Father), Henry James Ball (Son) and Francis Andrew Ball (Son), general lightermen and contractors of North Fremantle for £755. They were members of the firm of Ball & Sons of North Fremantle, Seamen & Contractors.

Devoid of any previous diving experience, Harry practised in the smooth water by the Fremantle bridge. The vessel was uninsured and represented the entire savings of the Ball family. Prior to the Venus, James Ball had purchased the Hopeful, renaming it Florrie. This boat brought across 1500-tons of stone from Rottnest in the construction of a new wing to the Fremantle Prison.

The West Australian Newspaper described her in 1923, “The Venus is not an imposing looking craft, and she belied her name. A vessel of some 60-tons, she gives the impression that she has been made up of the sum of the many odds and ends that have been worn from the old boats that have gone down around Fremantle. Her top hamper was a strange mixture of dignity and incongruity, but her hull appeared comfortably solid.”

The Venus was well known at Fremantle for salvage services rendered. These included the salvage of the Orizaba, near Garden Island in 1905 and the Pericles, off Cape Leeuwin in 1910.

In 1918, the hulk, Tamerlane, was run down and sunk by the Dimboola in the fairway of the inner harbour at Fremantle, the Venus being used to raise the hulk by means of a coffer-dam erected around the sunken ship. On 17 October 1920, the Venus’ seacocks were opened in what appears to have been an act of sabotage. It filled and sank but was subsequently raised. In May 1923, the Rottnest Board of Control had made arrangements with the Venus to maintain a fortnightly service to the island throughout the winter and was also making regular trips to Garden Island and Rockingham.

At 9:00am on 13 August 1923, the Venus left for the Abrolhos Islands, calling in at Rottnest Island to pick up two crewmen, one of whom was Manuel Collell, the caretaker of Government House on the Island.

The 6 crew that day were:

Francis (Frank) Andrew Ball, Captain (35)

Henry (Harry) James Ball, Engineer (40)

Charles Aslesen, Deckhand and Crayfisherman (35)

Thomas Hopkins, Fireman (around 60 years of age)

John Hillary (Jack) Malone, Deckhand and son-in-law of James Ball (45)

(Juan) Manuel Collell (40), a Spaniard by birth and crayfisherman who supplied the craypots for the expedition.

According to Frank Ball, the vessel sailed from Rottnest Island on the 14 August heading for the Abrolhos, arriving on Wednesday 15 August at 6pm. The Venus had planned to leave the Islands on the 19 August, but owing to bad weather remained in shelter at Gun Island for the night. They finally left the Abrolhos Islands at 8am on Monday, 20 August 1923. The weather was reported as fair all day until nightfall when it commenced to blow. It was then too late and dark to make for Jurien Bay (the nearest shelter at the time) so the only thing left was to “run before the gale”. The wind was North West, gradually veering to the West.

At 9pm the full force of the wind and waves struck the vessel. It worsened by 1:30am on the 21 August, and at that time Frank Ball decided to get life belts up for the crew – eight were produced, but a little later some were washed overboard. At 3:30am he went below to change his clothes, leaving Aslesen at the wheel. On returning to deck at 4:00am he was talking to Aslesen who considered they were 25 miles off the coast. Just at that moment he noticed an enormous breaker bearing down on the boat. It struck the starboard side and washed completely over the top deck. He gripped the rail with both hands and managed to wedge his feet and legs in the deck fittings. Aslesen went overboard having lost his hold on the wheel and was never seen again. He had no lifebuoy or belt on, and was wearing a heavy coat. Frank later realised they had hit and been carried over the three mile reefs. All the fresh water was lost when the boat struck the reef.

Frank Ball instructed Collell and Malone to get the hand pumps moving to remove water from the engine room. A little later, another large wave struck the boat starboard side, and wrenched the steam pipe from the boilers causing the steam to escape. Initially it was thought to be the main pipe, but later examination revealed it was a smaller pipe. Both men on the pump were washed down the stokehold, and the lights went out.

Harry Ball had emerged from the engine room, which by this time was flooded, and had said that there was nothing left to do but to jump overboard. It was very dark, and they still considered they were some distance off the Coast. Frank Ball was of the opinion the Venus would weather the storm, but his brother Harry was afraid that if the vessel was swamped they would all be sucked down with her. He had placed a lifebuoy around his neck and donned a lifebelt and was ready to “jump ship”. The bulwark on the lee side had previously been washed away. Not knowing exactly how far from the shore they were, they all decided to stay with the ship for as long as possible. At that time it was 4:35am. Collell fixed the jib sail and endeavoured with the help of steering gear to keep the boat stern to the weather, but to no avail. Two further breakers approached the starboard side and struck the boat heeling over to the Port side. Harry Ball lost his hold and went overboard. Frank called out to his brother to see if he was okay and he stated, “Yes I am alright”. He was said to be a strong swimmer with experience in diving during salvage operations, and initially Frank considered that he would safely wash up on the beach.

At about 6am just as day was breaking they saw cliffs on the port side. They had spent the whole time keeping the vessel afloat by baling out water. Despite dropping anchor the boat drifted towards the shore, missing the rocks and landed on a small beach where the vessel was wedged firm. The four men got ashore by climbing over the bow into two feet six inches of water. Malone and Ball made a search for the missing men, two miles North and South of the spot, but found no trace.

At 8am, the two younger men, Ball and Collell, left behind Malone and Hopkins to search for assistance inland. They eventually reached Mr. W.R. McCormick of Waterville, at Gingin Brook at 5:45pm the same day. They had walked 16 miles to reach the McCormick farm, locating it through repeated climbing of the trees and searching through field glasses. The Gingin Police were telephoned and Constable Trecardo reached them at 8pm.

The Gingin Police did not find the site of the wreck until over 12 hours later, having searched all night, and when they found the two remaining survivors they were in a very exhausted condition. The following evening they were joined by Hopkins and Malone and they later inspected the wreck, considered that it could be saved.

Concerning the vessel, Frank Ball was optimistic, “There is really nothing seriously wrong with her, and it is only clearing up and oiling that is required. The damaged steam pipe I can fix in about half an hour, and, given easterly winds, I am practically sure that she can be re-floated.”

The beach was scoured by a search party for a nine-miles radius until 3pm Wednesday, but no sign of the missing men was found. Police Constable Trecardo later found a lifebuoy and lifebelt with broken strings about nine miles North of the wreck, but no trace of the missing men.

In October, a salvage party was sent to the wreck but was unsuccessful in re-floating her.

The Seaflower was wrecked the same year about five miles south of where the Venus was stranded and the salvage team that revisited the site re-buried one of the men from this wreck.

James and Frank Ball stayed behind camping on the beach waiting for a favourable opportunity to re-float her, but it was all in vain. Various items were salvaged, but there were no further traces of the missing men. Ball & Sons had successfully re-floated many other abandoned craft, but they could not salvage the Venus. The vessel which had saved so many other vessels, could not be saved herself. She was firmly embedded in three feet of sand, with large holes forced into the ship’s keel.

Frank and Harry Ball had sailed together for 25 years. They married sisters, and four years prior to the tragedy, Harry’s wife Beatrice died, and he re-married a third sister. He left behind a wife, Jessie Waldron, and five children. Frank became the firm’s diver once Harry had passed away, and with his father, they purchased the Agnes to replace the Venus and later utilised the boiler from the wrecking of the Duchess to carry forward their salvage works.

Charles Aslesen (or Allenson, or Atlesen, or Asleson) was a native of Norway, of short stout build and about 35 years of age. Aslesen expressed a wish to see the Abrolhos Islands and had accompanied the crew as an onlooker. He apparently had an intimate knowledge of the coast and the islands, and was said to be a fisherman who had been all over the State working in various capacities. When ashore he led “a loose life” and drank heavily. He left behind virtually no personal effects and no relatives in the State. The newspapers incorrectly published Charles Anderson as his name, as the Ball’s had previously engaged a man by that name from North Fremantle.

The Venus’ final resting place is about 11 miles North of the Mouth of Moore River, or nine kilometres south of Ledge Point town. The boiler partly shows above water about eight metres offshore at low tide. The axis of the wreck is almost bow on to the beach. Some frames and hull planking remain along with a few other artefacts. The ship’s wheel, off the Venus, has been recovered and conserved by the Western Australian Museum. The ship’s compass had an even more interesting journey. It originally belonged to the survey ship, Victoria, later finding its way onto the Government Steamer, Penguin, which was wrecked on Middle Island in 1920. Messrs. Ball and Sons purchased it from the wreck and had it installed on the Venus. After the Venus was wrecked it was purchased by a private collector, Dr. H.H. Field-Martel.

More of the maritime history of Western Australia can be associated with the steamer Venus than any other single vessel on the coast. Dating back many years – the wharf sages relate it in their reminiscences – the Venus traded along the coast, carrying provisions and assorted merchandise between little-known landing places. It was probably one of the earliest engine vessels to be used in the rock lobster industry in this State, at a time when most boats were small sailing craft and most of the lobster catch was used for bait.