Captain A. E. Trivett

Vessel Name: Captain A. E. Trivett

Judy Kathleen Webster

Drowned at Sea; Body never recovered

13 June 1975

The Captain A. E. Trivett as appeared in Australian Fisheries Magazine 1972

The Captain A. E. Trivett in Shark Bay, 1972

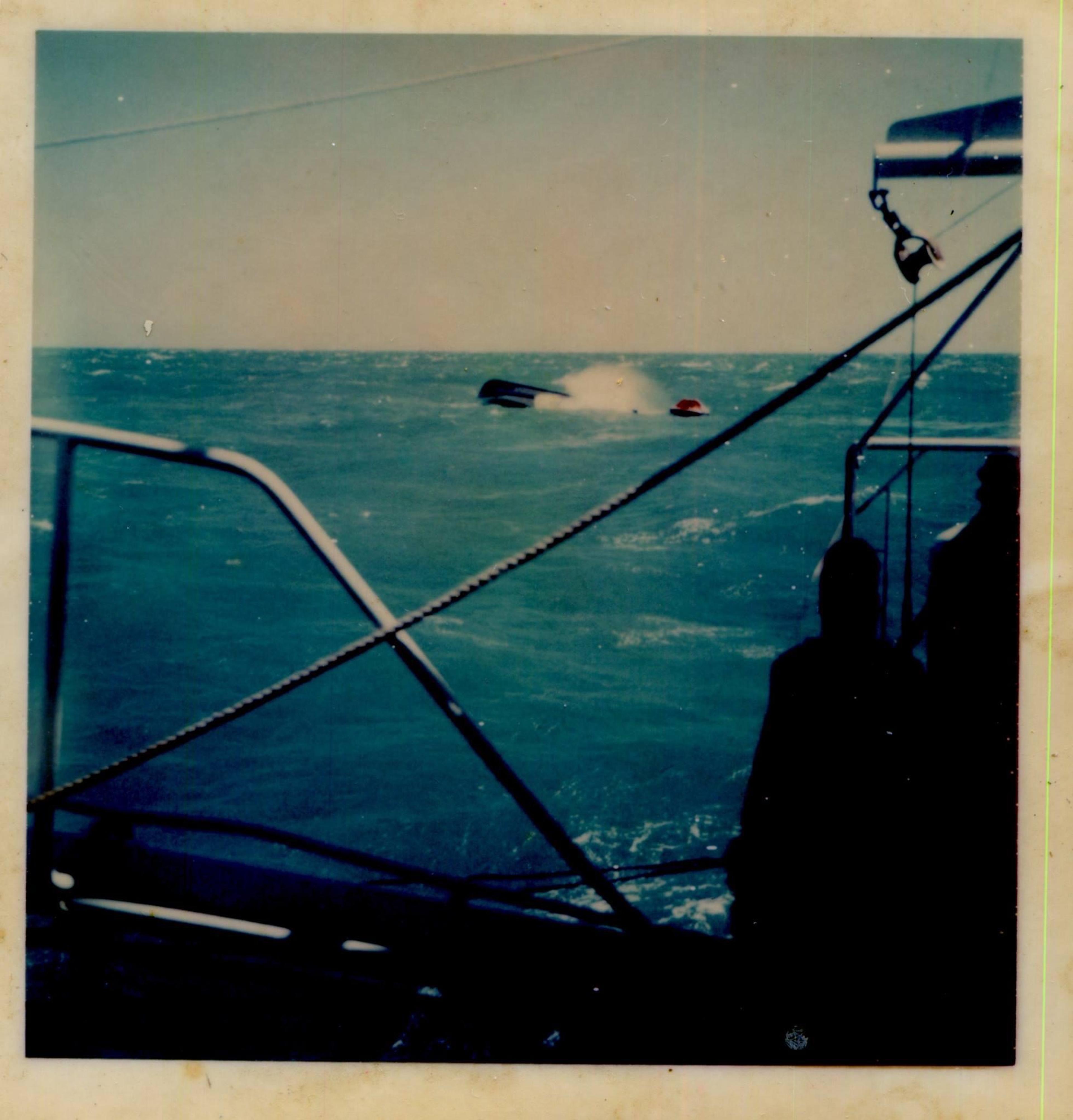

Photo of the Trivett taken from the Kaigel

Photo of the Hull off the Trivett taken on the Kaigel

An RAN Grumman Tracker anti-submarine bomber searched from the air

Photo of the Hull off the Trivett taken on the Kaigel

HMAS Adroit arrives at the scene

Photo of Gemini and Shenton Bluff

The M.V. Captain A. E. Trivett was named after a former Fremantle harbour master, Captain Albert Ernest Trivett. Captain Trivett was a Fremantle Pilot from 1920 until 1943 and Harbourmaster from 1943 until 1953. He retired in 1953 but maintained an active interest in the harbour with his teaching. He helped many West Australian fishermen to meet their seamanship requirements and was well-respected amongst these circles. He had tutored many Fishermen, including members of the Lombardo family. His wife, Mrs Gwendoline Trivett, B.E.M, devoted her entire life to community service. In addition to her work with the Red Cross, she volunteered for more than 40 years in Fremantle Hospital and was well known for her work with needy merchant seamen, fishermen, migrants and all travellers.

Captain Trivett passed away in August 1971.

The Dillingham designed vessel bearing his name was launched by his wife for the Lombardo Marine Group on Saturday 11 March 1972 in Fremantle. It was built at a cost of $255,000 by Ocean Shipyards and Offshore Engineering Services Pty Ltd of Fremantle WA (both companies were associates of the Lombardo Marine Group of Fremantle) and owned by Kia-Ora Fisheries Pty Ltd. Its construction took place in the company’s own slip at Fremantle Fishermen’s Harbour. Michele (Mick) Lombardo was the chairman of Kia Ora Fisheries and Lombardo Marine Group. At the time, it was one of five trawlers owned by the company. The Gemini was another. There were three other trawlers working out of Shark Bay.

The Captain A. E. Trivett had the latest equipment. It was a 77 foot steel trawler designed to operate for long periods, and it carried more fuel and water compared to vessels of a similar size. It had a 14,000 gallon fuel capacity and a 3,000 gallon water capacity. It had freezer space for 60,000 lb of product. To achieve longer periods of operation, many of the control systems were duplicated to ensure against breakdowns. It had a 22 foot beam and 10 foot draft, with a gross tonnage of 166 tons. It was fitted with a Gylot steering console and a gyro and magnetic auto-pilot. The wheelhouse and six cabins were air-conditioned. The bridge deck had the skipper’s quarters situated at the rear. There was a hot-water system for the galley and the three shower units, and there was a split level galley stove with grill and wall oven. The trawl winches were electric-hydraulic.

The Captain A. E. Trivett had been in Fremantle at the end of 1974 for a major refit. It left Fremantle in December with the intention of fishing in the Gulf of Carpentaria. All crew members for this trip had been recruited in Perth and Fremantle, but some crew had later disembarked in Darwin. The Skipper, Harcourt (Hark) Waller had been working on trawlers for 11 years and had skippered them for the last 8 years without any mishap. The Captain A. E. Trivett was his first command with the Lombardo group. He had two young children at the time.

John Adams had just arrived back in Perth in November 1975 after spending 12 months in Europe. Part of that time he had spent working on a Grimsby trawler named the Ross Leopard, cod fishing in the North Sea. He came from a long line of sea-farers, and his family were no strangers to the perils of the sea. One uncle, Cecil Adams, was the Skipper (and sole survivor) of a deep-sea trawler called the Bluff, which sank in the Atlantic. Adams was in need of a job so he answered an advert for a 1st Mate position on a 23 foot prawn trawler licensed to fish the northern waters of Australia, including the Gulf of Carpentaria. Vince Lombardo interviewed Adams for the position on the Captain A. E. Trivett.

By December 1974, the vessel was ready for departure. Mrs Gwendoline Trivett came to where the vessel was berthed in the Fremantle Fishing Boat Harbour. She wished the crew farewell and a safe and prosperous voyage. Her parting words were, ‘Please look after this vessel as it bears my husband’s name’. A Portrait of Captain Trivett displayed proudly in the wheelhouse kept a watchful eye on everyone onboard.

On the morning of the 13 June 1975, the vessel capsized and sank. It was not trawling when it capsized but some reports state it was proceeding with its booms extended. The sea conditions were reported as moderate abaft the port beam, with 50 km/hr winds and 6 foot waves.

This is John Adams' (1st Mate) account off what happened 48 years later, written on the 25 April 2023;

‘The Captain Trivett departed Fremantle in December 1974 enroute to the Gulf of Carpentaria in Queensland. The voyage to the Gulf was fairly uneventful, except for a few minor occurrences. During the night our course sometimes crossed the paths of Taiwanese fishing boats, it was tricky navigating through the long lines they set covering long distances across the ocean surface, requiring extra look-outs at night, the risk of fouling the vessels propeller or getting tangled up in these lines was never far from one’s mind.

During the voyage out from Broome the vessel encountered massive following seas; I was astounded at the size of the swells and waves behind us. The swells were bigger than any other I had ever experienced before. I had fished in the North Sea and Skippered vessels in the Bass Strait off the Victorian Coast but never can I remember seeing swells and waves that big.

It was common for trawlers traveling from Fremantle to the Gulf of Carpentaria to take a short pass through the Kimberly’s to save time and fuel. Skipper Hark Waller decide to take the short cut, navigating at night using radar, we passed through Voltaire passage during an ebbing spring tide which uncover and exposed many of the surrounding reefs. This created a large amount of clutter on the radar screen, making it difficult to accurately fix the vessels position. The Skipper decided it was too dangerous to proceed, the vessel was stopped and anchored, we patiently waited for the tide to rise over the exposed reefs, before fixing the vessels position and proceeding to Troughton Island, through a maze of reefs and Islands. Once at Troughton Island it was a nice clear run across Joseph Bonaparte Gulf to Darwin.

The voyage to the Gulf of Carpentaria took 20 days. On arrival, the Captain Trivet immediately started fishing for Banana prawns. Unfortunately there was not a lot of prawns to be had, many of the other vessels in the fleet were experiencing low catch rates.

A meeting then took place between Burt Griggs, Skipper of the 23 metre Gemini, Ken Leech Skipper of the 23 metre Kaigel and Hark Waller Skipper of the 23 metre Captain Trivett. The outcome of the meeting was that all three trawlers would proceed to Admiralty Gulf in the Kimberley, where a moon phase was going to occur that could result in the aggregations of large schools of Bananas prawns. All three crews where very excited about the trip and the prospect of earning some money. At that time there was a lot of pressure on the Skippers to return a profit.

The three trawlers silently departed the Gulf of Carpentaria in somewhat secrecy; the three Skippers did not want the other Trawler Skippers to know what they were up to. The Captain Trivett was one of the very few Trawlers to be fitted with a Gyro Compass. It also had a state of the art auto pilot steering system, the distance to be travelled between the Gulf of Carpentaria to Admiralty Gulf was approximately 1000 nautical miles. It was decided that Captain Trivett would lead the way, followed by Gemini and Kaigel which both used magnetic steering compasses to navigate.

Before departing the Gulf of Carpentaria three crew members left the vessel, which was a blessing for them because on Black Friday 13th June 1975 the Captain Trivett capsized half way across Joseph Bonaparte Gulf off the coast of Western Australia.

At the time of the capsize the Captain Trivett crew consisted of;

Harcourt (Hark) Allan Keith Waller (Skipper), 29

John Adams (First Mate), 23

Nikica (Nick) Cicmirko (Engineer), 44

Cynthia Martin (Crew), and

Judy Kathleen Webster (Cook), 18

The navigation watches where split between the Skipper and the 1st Mate.

The vessels position was approximately Latitude13 ͦ 10' S, Longitude 128 ͦ 20' E, steering a course towards Troughton Island. I had been on watch most of the night, when Skipper Hark Waller relieved me about 4:30 am. It was still dark, and I was very tired and was looking forward to some undisturbed sleep. Whilst asleep at approximately 7:30 in the morning I heard the engine revs change, my first thought was - why had the Skipper dropped the engine revs - maybe there were Taiwanese long liners ahead. I decided to get up and see what was going on.

As I was making my way through the crews sleeping quarters I could feel the vessel listing and I knew something was wrong. I climbed up the accommodation ladder and entered the main Galley area. Cynthia Martin must have also been alarmed as she was right behind me. Nick the engineer was in the galley I could see his hands in the air and he was saying ‘what the F#@k is going on!’

I immediately felt something was very wrong. The vessel was now listing to starboard, within seconds the list increased. I knew I had to get out of the galley quickly and on to the aft deck. When I got out on deck I could see the starboard gunnel was close to the water line, I could not stand on the deck as the angle was too steep. I then ran along the top of the Port gunnel towards the stern and dived over the side, when I landed in the water I thought - I hope the Skipper does not put the engine astern as I could get caught up in the propeller.

Wearing just my jocks, I dived over the stern into the water. I swam around to the leeward side of the vessel and could see the port trawl boom was now reaching towards the sky at a 90 degrees angle. Within seconds the boom fell to the water line and the vessel was fully capsized. I saw Nick the Engineer trying to get up onto the overturned hull. I could not see anyone else, then suddenly Skipper Hark Waller popped up from underneath the capsized vessel like a cork. There was no time to grab life jackets it was a crash abandonment. I found a floating half empty Freon 12 gas cylinder. Nick then appeared along side of me, he did not look good - his face was completely grey, he did not have anything to keep himself afloat so I gave Nick the Gas bottle and found a floating piece of marine plywood to lie on. I looked at the capsized vessel and the thought that came to my mind was how quickly life can change, it was a mess - debris floating everywhere. The water surface was covered in diesel oil - you could not see it but you could taste it in your mouth. The upturned wheel house was still half submerged, the water level inside the wheel house was about half way up the window’s. It was then I saw Judy Webster’s face inside the wheel house looking out at me, we both looked at each other, until the water level rose above the windows when I lost sight of her, and I knew she was trapped in an air pocket.

The hydrostatic release securing the life rafts released them. They both immediately inflated, bobbing like two corks alongside the upturned hull - the painter lines where still attached to the vessels side rails preventing them from floating away from the vessel. Skipper Hark Waller yelled out “I am going to get the life rafts” I yelled out to Hark, “Hark Hark I will come and help you, everyone in the water thought I was yelling out “Shark Shark!” I will come and help you. My thoughts were, we would spend at least two days in the life raft before being rescued.

Then behold, the Gemini appeared, I now realised why Gemini had seen us! They were traveling directly behind. Later during a conversation with Skipper Burt Griggs he said, "whilst sitting comfortably in the wheelhouse I noticed a trawl boom 90 degrees in the air and thought I had better take a closer look at that” only to discover the boom belonged to the Captain Trivett.

Gemini immediately heaved to alongside the stricken Trivett, she laid beam on to the sea, and at times was rolling dangerously, from side to side. Abandoning the Trivett in gale force winds was the easy part, I knew being rescued and getting on-board the Gemini was not going to be easy. I thought it was far too dangerous to try and get back on board Gemini via the lower deck, I thought my best bet would be to wait until Gemini rolled to starboard grab the top part of the stabiliser chain on the boom and pull myself up onto the boom, then work my way along the boom back on to the main deck. This proved to be a serious mistake. When the Gemini rolled heavily to starboard, I grabbed the stabiliser chain, when it then rolled back to port I was immediately catapulted up into the air, the chain ran through my wet hands and along the side of my head nearly knocking me out, I quickly let go of the chain and drooped back into the water narrowly missing the metal stabiliser on the way down. If any part of my body had hit the stabiliser I would have suffered a serious injury.

Back in the water I noticed Garry Ray (the Engineer) on the back deck, I swam close to the side of the Gemini’s hull, waited until the vessel rolled to starboard, then swam directly alongside the hull and put both hands into the air. Gary grabbed me at the precise moment and lifted me out of the water and onto the main deck - it was his split second timing and strength that saved my life, because if he had not grabbed me the next time the vessel rolled over to starboard it would have come crashing down on my head.

Skipper (Hark Waller), Engineer (Nick Cicmirko) and Crew (Cynthia Martin) were rescued from the bow with a rope. It would have required an enormous amount of strength and determination to lift a person up 6 meters from the water line up onto the bow with a rope. I did not think it was possible that is why I did not attempt it. The crew from the Gemini later told me they watched in horror as I attempted to get on board via the starboard booms stabiliser chain.

The Gemini returned all four survivors to the Port of Broome where they were repatriated to Perth.’ - END

When the vessel capsized, the nearby Kaigel put out a MAYDAY call over the radio but it took some time before emergency response answered. Sergeant Jim Rule and Constable Neville Cosgrove, of the Wyndham Police, were heading for the scene in a Harbour and Light Department vessel, the Cambridge. Peter Wales, the Engineer from the Kaigel managed to swim to the stern of the capsized vessel. He tied a large Dan Buoy fitted with an aluminium radar reflector and a flashing light to a piece of prawn net trailing behind the submerged surging stern. With both booms out and the vessel surging up and down in heavy seas, a lot of the rigging wire and floating debris were still attached to the vessel. The Kaigel then stood off a distance to avoid striking it because of the high seas. The blinking light that was attached went out shortly before dawn when the hull disappeared below the ocean. The Lloyd’s of London Marine Insurer Report of June 1975 has the location at approximately 13 50. S, 128. 30 E. It was 160km (100 miles) north of Wyndham.

Newspapers had reported that the crew of the Kaigel could hear noise of items being thrown about inside, possibly by a survivor, but in reality given the weather conditions, it would have been impossible to climb onto a heavily surging and wet upturned hull to listen for survivors. There were also other instances where the print media got the story wrong, suggesting that the two vessels had slung lines under the stricken vessel to keep it from sinking.

Navy and air force units from Darwin, Broome and Dampier were involved in the rescue attempt. HMAS Adroit, a Darwin gunboat was expected to arrive at the scene at 2:30pm that same day but it was delayed. It would act as the search and rescue co-ordinator. Marine Operations Centre in Canberra was responsible for the communication. One of the criticisms of the search and rescue efforts, was that all radio communications with the Navy had to go through Canberra. There was a call to have a direct radio link between boats and aircraft involved in sea rescue operations. These calls were echoed by Michael Kailis of M. G. Kailis Group.

There were other criticisms directed at the Navy, for the “noticeable lack of organisation in rescue efforts of the Royal Australian Navy”. Some even called for a coast guard, with its own rescue aircraft. Dick Verboon, operator of two trawlers in Northern waters also criticised the lack of air sea rescue equipment on the coast, noting the rescuers arrived 24 hours after the tragedy occurred.

Navy Grumman tracker aircraft from Broome flew to Dampier to pick up six divers from the mine sweeper HMAS Ibis, who were doing survey work in that area. They flew the divers and their equipment to Kununurra. An RAAF Iroquois helicopter, flown in from Darwin was to have ferried them to Lacrosse Island at the mouth of Cambridge Gulf, but darkness beat them. Attempts to get navy divers to the scene on the same day had to be abandoned because a vital link in the transport chain, a helicopter, could not fly at night. The leader of the diving party which was taken to Kununurra from Dampier, Lieutenant Vic Rashleigh, acknowledged it had been necessary to travel by Grumman Tracker aircraft because civil aircraft were not allowed to carry divers’ gas cylinders. The Diving team had been involved in the rescue of two crewman from the Floodbird in Darwin Harbour during Cyclone Tracey. An RAN Grumman Tracker anti-submarine bomber searched from the air. The search was called off two days later and three search flights failed to locate any trace of the vessel.

In 1976, the Commonwealth Department of Transport published Parliamentary Paper No. 375/1976 and gave the following description for the Captain A. E. Trivett tragedy:

“The Captain A. E. Trivett, a 23-metre Australian prawn trawler, capsized and sank in Joseph Bonaparte Gulf (W.A), during bad weather on 13 June 1975. One crew member is missing, believed drowned. Four survivors were rescued by Gemini, another trawler, which had been accompanying the Captain A. E. Trivett. A preliminary investigation into the casualty concluded that the most probable cause of the capsize was a loss of stability brought about by a number of partially filled fuel and water tanks, and the ship’s course related to the prevailing wave pattern.”

Judy Kathleen Webster was from Prahran in Melbourne. She was the only child of Harold and Ilse Ruth Webster. The last letter she wrote to her Parents was published in the Sunday Times of the 15 June 1975. It read:

Dear Mum and Dad.

In two months I have made only $400 or so and that was mainly due in the first few weeks so I’ll probably be heading home soon.

We should go to Darwin in two or three weeks and I think I’ll get off then.

Please don’t send me any more mail until you hear otherwise.

This letter is also to say “Happy Birthday” to you Daddy and I hope it’s (the letter) in time. There isn’t much more to say except I love you.

See you soon.

Lots of love.

Judy X X X X

PS Give my love to Omi (grandmother) and David.

Sorry it is short but another boat is taking it to post.