Rosette

Vessel Name: Rosette

Captain Vincenzo Vukovich, known as John Vincent

Mate John Beaty

5 unidentified crew members

George Fisher

Robert Ramsay

Thomas [Tom] Ralston

Henry Palmer

Harley Landor

M.A. Fogalstrom

Constable Bogue, his wife and three children

Lost at sea; bodies never recovered

24 January 1879

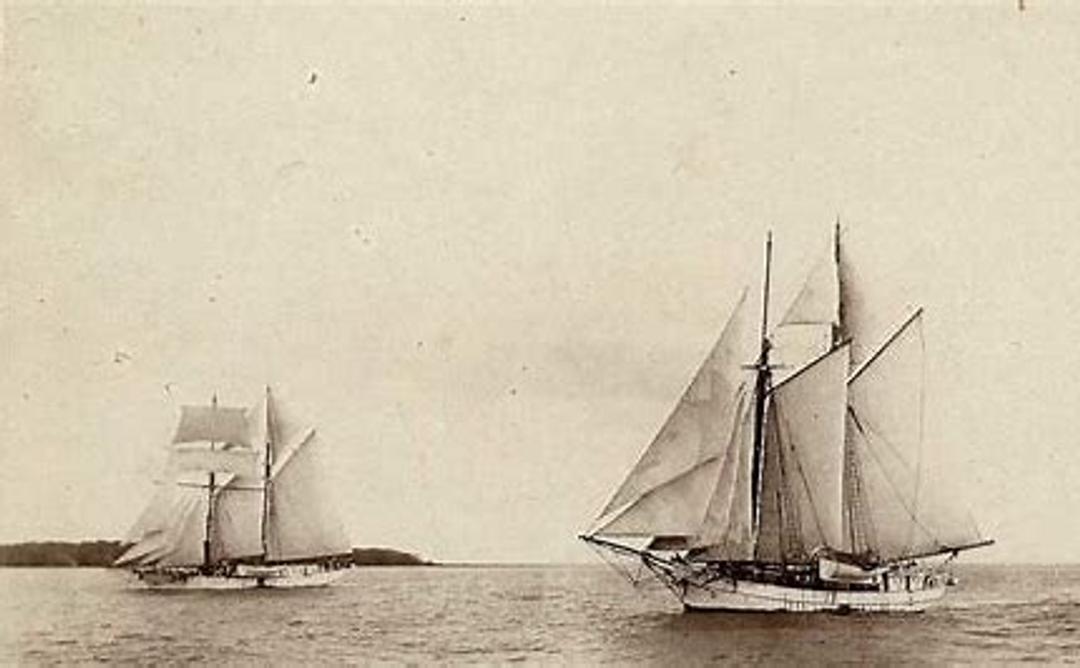

Photo from WA Museum

Rosette was a 67-ton schooner built in Perth in 1874 by the well-known Laurence Brothers for Jim Storey for use in the pearling industry as a transport/coastal vessel. Like many of the schooners she picked up pearl shells and took them to Perth but also paid her way by carting freight and passengers (replacement crews, boat owners, pearl buyers, investors) for the return trip to pearling grounds.

Rosette was 21.5 metres long, 5.5 metres across her beam, and she drew 2.4 metres of water. She was registered in Fremantle with official number 61117. She was a busy vessel and carried a crew of six. They covered the pearling grounds and coastal settlements between Fremantle and Port Walcott [formerly Tien Tsin Harbour and now called Cossack].

On a voyage to Port Walcott in January 1879 Rosette was in the charge of Captain John Vincent and mate John Beaty. There were five other crew members who unfortunately remain nameless. Rosette was owned by Dalgety Moore and she was making her way to Port Walcott to collect pearl shell.

Vincenzo "Vicko" Vuković was the first known Croatian settler in Western Australia. He anglicised his name in Australia as many immigrants did. It helped them to find work and be accepted into society. He emigrated in 1858 from the island of Šipanj. John married Bridget Russell, an Irish woman, in 1879.They had five children.

There were passengers aboard: George Fisher, Robert Ramsay, Thomas Ralston, Henry Palmer, Harley Landor, M.A. Fogalstrom, Richard Jewell, Police Constable Bogue, his wife and three children. George Fisher, Thomas Ralston, Harley Landor and Richard Jewell were friends and colleagues who were involved with connecting the telegraph line from Western Australia and the eastern states. Police Constable Bogue was on his way to a new posting.

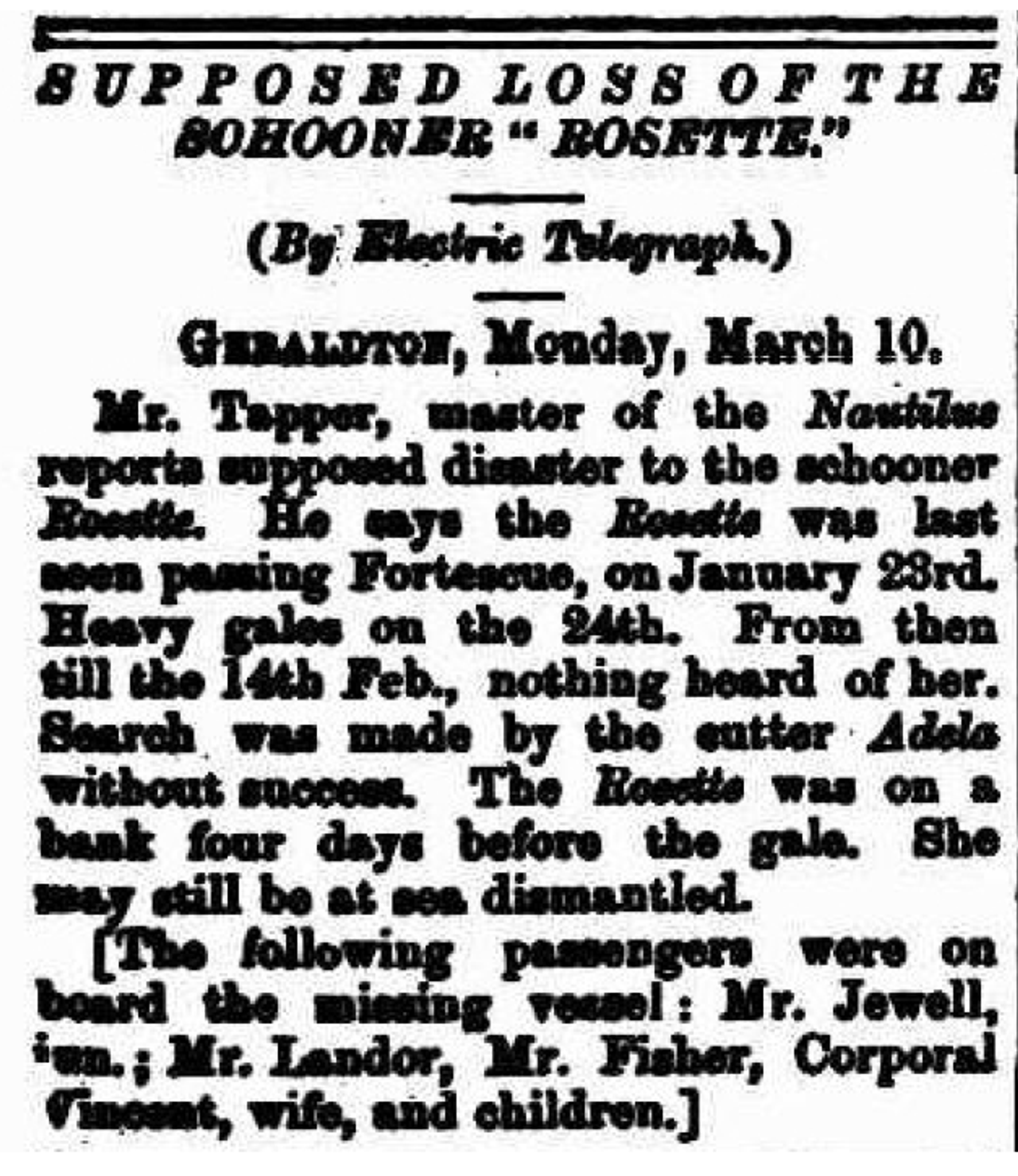

Rosette met with the schooner Industry on 24 January and Captain Vincent dined aboard the Industry with master Valentine Hester. At that time Rosette was aground on a sand bar at Thompsons Island in the Dampier Archipelago. Captain Vincent said he could float Rosette off with the evening tide.

Rosette left Industry in Flying Foam Passage on 24 January. It was the last time she or the 19 souls aboard her were seen.

On the night of 24 January, after Rosette and Industry parted company, the wind gained velocity and overnight turned into a gale. Rosette stood to anchor, waiting until the gales blew over.

When Rosette did not arrive at Port Walcott and had not called in to any of the coastal ports for repairs or to replenish supplies, concern for her prompted a search. On 24 March 1879, the revenue cutter Gertrude mastered by Captain Pemberton Walcott was tasked with finding the vessel and the people aboard her. Captain Walcott was a well-known and popular skipper who could be counted on to conduct a thorough search using all the resources at his disposal.

A revenue cutter was a vessel responsible for carrying pearl and pearl shell south and each pearler paid a sum of money to maintain the revenue vessel. Revenue vessels also carried mail and government documents and officials. Pearlers were displeased when their revenue vessel was taken off her usual schedule as it meant their precious cargo was delayed in its voyage to the sellers.

On this occasion the resident magistrate could not find a suitable vessel available for charter, and he made the decision to instruct Gertrude to carry out the search. Captain Walcott sailed with all haste, hoping to find survivors washed up on one of the nearby islands. He sketched a survey of the areas to search for the Rosette. These survey sketches served as navigational charts for the area after the event.

Police Sergeant Vincent and James Fisher (brother to passenger George Fisher) were instrumental in the search of island coasts. James was sure he could find his brother and continued to search long after it became clear that there were no survivors from the Rosette.

On 11 February Sergeant Vincent reported there was no trace of the Rosette, and there were no reports of sightings. Then, on 17 March word came from Master Kelly on the schooner Kate at Cossack. He had left Port Walcott sailing south, and he found Rosette, sunk at her anchors near Rosemary Island.

On 26 March Captain Walcott hastened from Cossack to Rosemary Island. He secured four divers he considered to be “the best on the WA coast”, and a lad called Turner who had been a passenger on the Kate. Turner could help locate the Rosette’s precise position. He arrived at 4pm and anchored approximately quarter of a mile from the wreck.

The Cygnet accompanied Gertrude and at 6am on 27 March she set two of her jollyboats to search for wreckage and survivors on the nearby islands. With crew of both boats searching Goodwyn Island, items from Rosette were found including flour, shooks [staves that make up hogsheads, barrels and boxes], cases and cabin fittings.

It was confirmed Rosette had sunk at her anchors and was sitting in approximately four and a half fathoms [8.23 metres] about 2 nautical miles [3.7 kms] from Rosemary Island. Her first anchor had 90 fathoms [164.6 metres] of chain, fully paid out while the second anchor had let go and was lying four or five yards [4.1 metres] from the bow. The hull was surrounded by the items thrown overboard to lighten her. The masts hung in the rigging having broken away as soon as the stays were cut.

On near Enderby Island, there was evidence that Mrs Bogue and the three children were lashed to a spar, which had come away from the boat. Remains of the lashings and clothing were found, but there was no sign of the bodies.

It appears Captain Vincent did all he could to outride the storm. He anchored fore and aft. When the winds blew harder, he discharged cargo and top hamper [structure above the hull that can create windage and instability]. When that did not work, Captain Vincent tried to cut away the masts, but it was clear they had broken away as soon as the rigging was cut. At last, the crew tried to get the boats away. There was no trace of them, and it is presumed they were swept away.

Two months after her sinking a box was found. The mail was wet but could still be delivered. Thomas [Tom] W. Ralston had stored a diary and records in the cash box that held the mail on board Rosette. Tom was 22 years old. At the height of the storm, he climbed to the topmast with Rosette’s ensign, determined she would go down bravely flying her colours.

Although there was visible evidence of the final harrowing hours of the vessel and her occupants, no traces of the souls aboard Rosette were ever found.