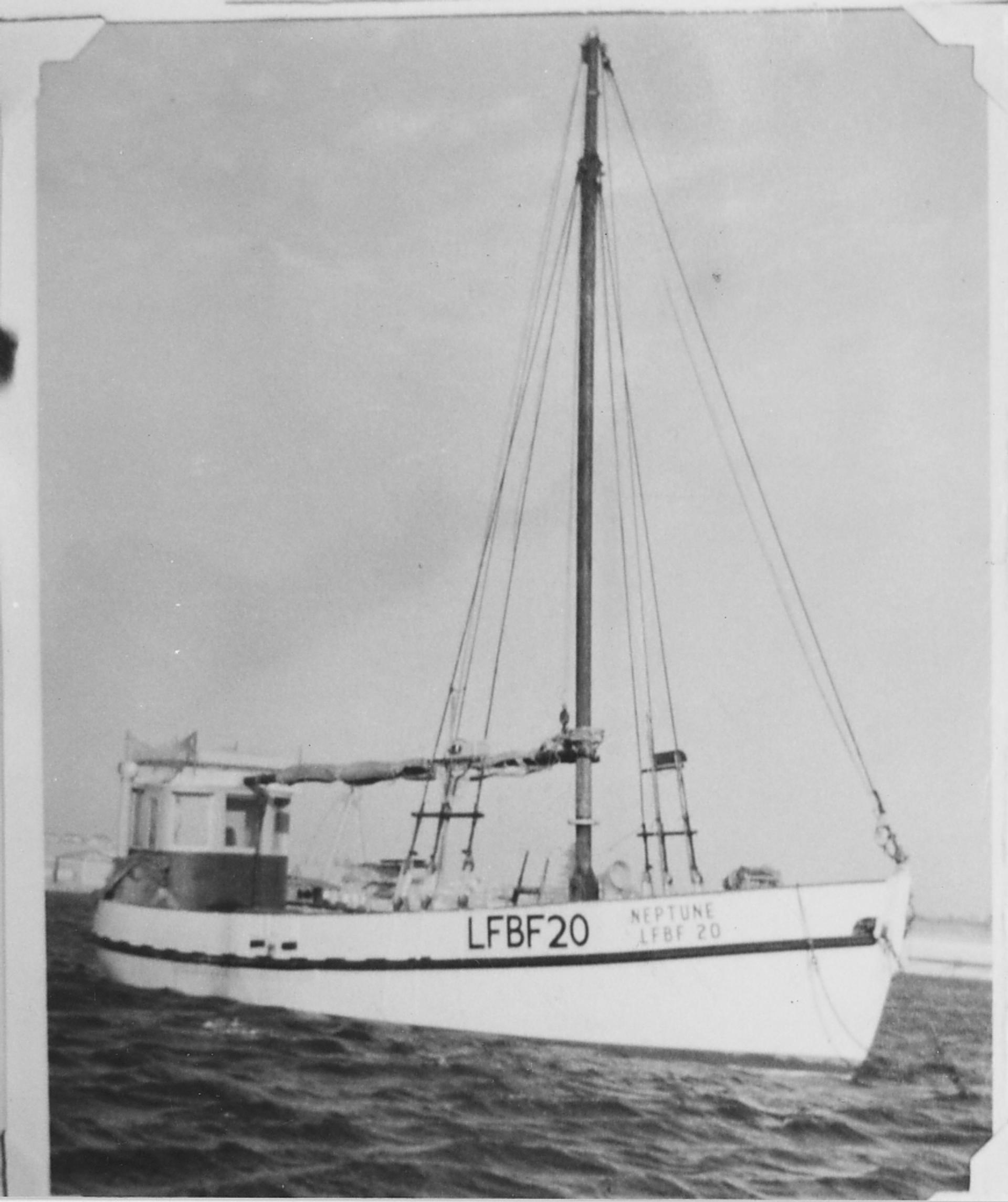

Neptune

Vessel Name: Neptune

Charles Jones

Lost at Sea; Unclear if body was ever recovered

13 June 1901

The 14 metre cutter Neptune

Florance Broadhurst

The Broadhurst Family

Photo by courtesy of Irwin Districts Historical Society

The Neptune was initially owned by George Shenton who used it to lighter cargo from the ships anchored in Fremantle’s outer harbour to wharves along the Swan River. It was sold to Charles Edward Broadhurst in 1885. He employed the vessel carrying supplies to the Abrolhos Islands, returning with cargoes of guano. Broadhurst mortgaged the cutter to John Bateman in September 1885 for £500 at 8%. The mortgage was discharged in June 1893 when ownership was transferred to Broadhurst’s son, Florance Constantine Broadhurst. The transfer resulting from the son buying the business from his father who then retired to England. Florance’s mercantile education, clear-sighted methods and organising power turned the tide of fortune and the business flourished. The younger Broadhurst continued to use the Neptune on the Geraldton to Abrolhos run and was the owner at the time it was wrecked. The vessel was not insured and an inquiry was not considered necessary.

In 1901 the Neptune was making her way from Geraldton to the Abrolhos Island and was caught in a violent gale and driven over breakers and rocks near the mouth of the Greenough River. It was wrecked near Walkaway, close to Mr. Duncan’s property at about 10pm on the night of Thursday 13 June 1901. Other vessels up and down the coast were damaged during this storm. The day prior the Neptune was seen out from Geraldton, and the manager at the Abrolhos, Mr. A. Davis who was in town anticipated she would make the Bay the following morning.

At the time of the tragedy, Charles Jones was the Master of the Neptune, and with him were Alex McKinnon and John Inglis. Inglis made a telephone call from Walkaway the following day stating that Jones was washed overboard and lost about fifteen miles along the coast to the south-west, and about ten miles from the shore. He stated, “We were running before the wind with only the mainsail set, and we ran on till noon. Yesterday the wind went west. We again set the mainsail and stood north. The wind hauled round sou’-west at about 10pm. We at last came in sight of breakers half a mile to the leeward. Our course was north-west by west. We then tried to put about but failed. We then wore her until she hit the breakers. The breakers broke overboard and we cast over a kedge; this however, would not hold her and we ran shore stern first, the boat being about twenty yards from the beach. The kedge pulled the winch clean out. The boat is now lying on the rocks and sand, the sails hanging loosely about her. There appears little prospect of recovery Jones’ body.”

Very little was known of Charles Jones. He was believed to be a Welshman by birth. Davis, the Manager at the Abrolhos stated that Jones was held in high value both for his merits and as a workman and companion. The Geraldton Advertiser detailed the events leading up to Jones’s tragedy, elaborating on some of the superstitions that befall a sailor;

“Inexpressibly sad were the circumstances of the death of poor Charlie Jones, who was knocked overboard by the gaff and the loose canvas of the mainsail while he was in the act of fastening it. The Neptune was at the time flying along with only her staysail set. During his connection with Geraldton and the Abrolhos Islands, Charlie Jones was liked and esteemed by his mates who looked upon him in the light of a decent, honest, hardworking man. Charlie must have had a presentiment of his early death by drowning, for he had a positive horror of the sea during the last few weeks of his life. His experience of a small boat in heavy weather was the cause of his relinquishment of a share in a recent fishing venture. The boat was swamped on one or two occasions and its occupants very nearly went down into Davy Jones’ locker. Last Saturday night week he walked to the old jetty in order to pull aboard the Neptune on which he slept. He slipped and fell into the water while in the act of stepping into the dingy at the landing-place. Drenched to the skin, he remarked on getting to land, “I’m bound to be drowned. I’ll not go aboard tonight but will go down and stay at mother’s” (meaning the mistress of his boarding-house). He did so. Just before he stepped into the dingy to convey him to the Neptune, which was on the eve of her fatal trip, he shook hands with a friend and said “Good-bye. I might never see you again.”. It was as if he had a premonition of his impending fate. He got permission from Mr. Broadhurst to take a friend with him on the last trip. That friend would have gone but for the entreaties of a lady who experienced a sense of coming evil and disaster in regard to the projected excursions. “What agony Charles Jones must have suffered in the few remaining moments of his life after he was knocked over the side? Battling with the angry waters of a tempestuous sea, his spirit must have been riven by despair. The Neptune was near at hand, yet there was no help for him. His two companions could hear his cries for assistance for the full space of a minute. They used their best endeavours, (unfortunately they were not sailor men) to get the boat towards him, but were reluctantly obliged to turn their attention to the task of saving their own lives. The Neptune was swept far out, out of reach of the cries of the drowning man, who was doomed to perish by that form of death he most dreaded. Charlie, it is stated, contributed what he could from his earnings towards the support of his mother and sister who reside, so it is believed, in Mary Street, Cardiff.”

Broadhurst continued to operate a successful guano mining operation on the Abrolhos Islands, often paying more than £16,000 a year in royalties. While digging for guano on Gun Island, the Chinese workers turned up artefacts such as bottles and tobacco boxes with Dutch inscriptions, beads and trinkets. Intrigued by these, and believing them to be relics of the Batavia, Broadhurst obtained a copy of an ancient book, Ongelukige Voyagie van’t Schip Batavia, a contemporary account of the Batavia tragedy. Excited by their discoveries, the family had the account published in the Western Mail newspaper, and thus exciting interest in Dutch shipwrecks. The artefacts were later identified as belonging to the ship Zeewyk. Broadhurst had done much to stimulate the attention of ornithologists and the general public with his great interest in the remarkable bird life of the Abrolhos Islands, and the Broadhurst family is synonymous with one of the earliest colonial pioneering families in Western Australia.

In February 1909, Broadhurst left to go fishing on the swan river in a small dingy but he did not return. His body was found lying face downwards in the sand, hanging over the edge of the boat. An inquest was held into his death. The jury returned the following verdict – “That the deceased, Florance Constantine Broadhurst, came to his death on February 19 from suffocation in the sand on the river ashore at Claremont, and that at the time of suffocation deceased was in an unconscious condition, caused by morphia, which he had been in the habit of taking for insomnia”.