Muriel

Vessel Name: Muriel

The Tender

Muriel

26 November 1913

Drowned; body not recovered

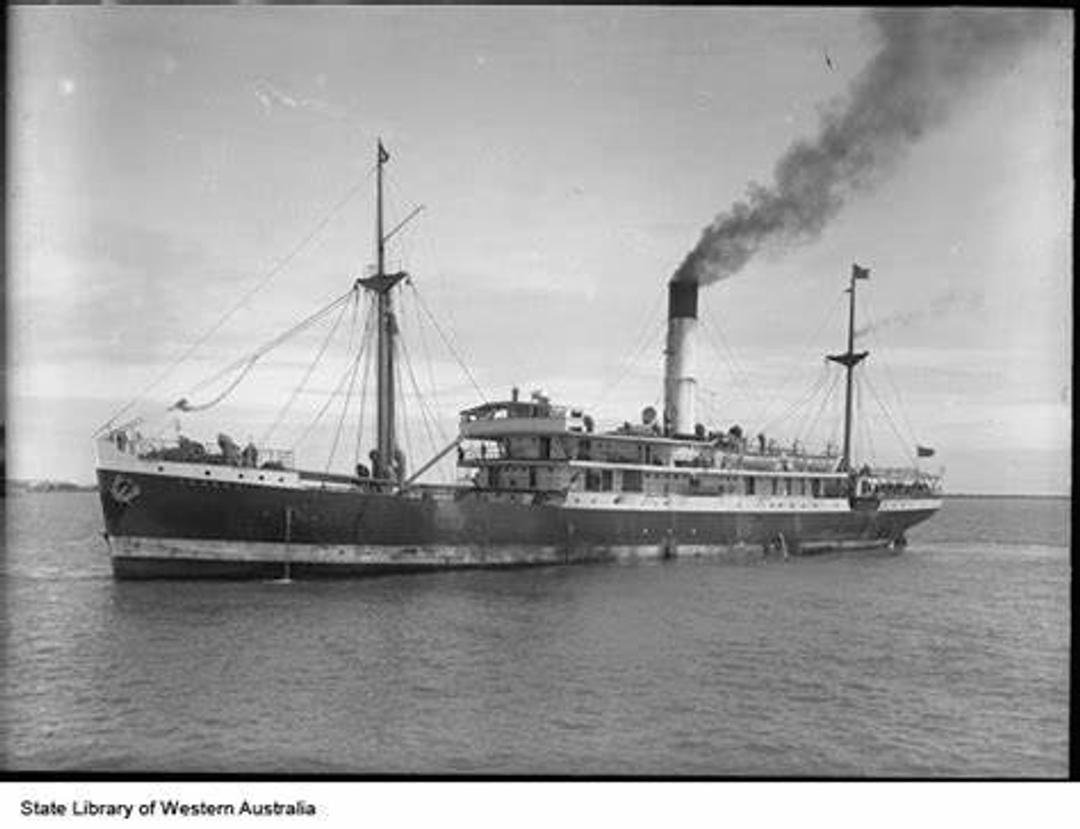

ss Charon

Courtesy State Library of WA

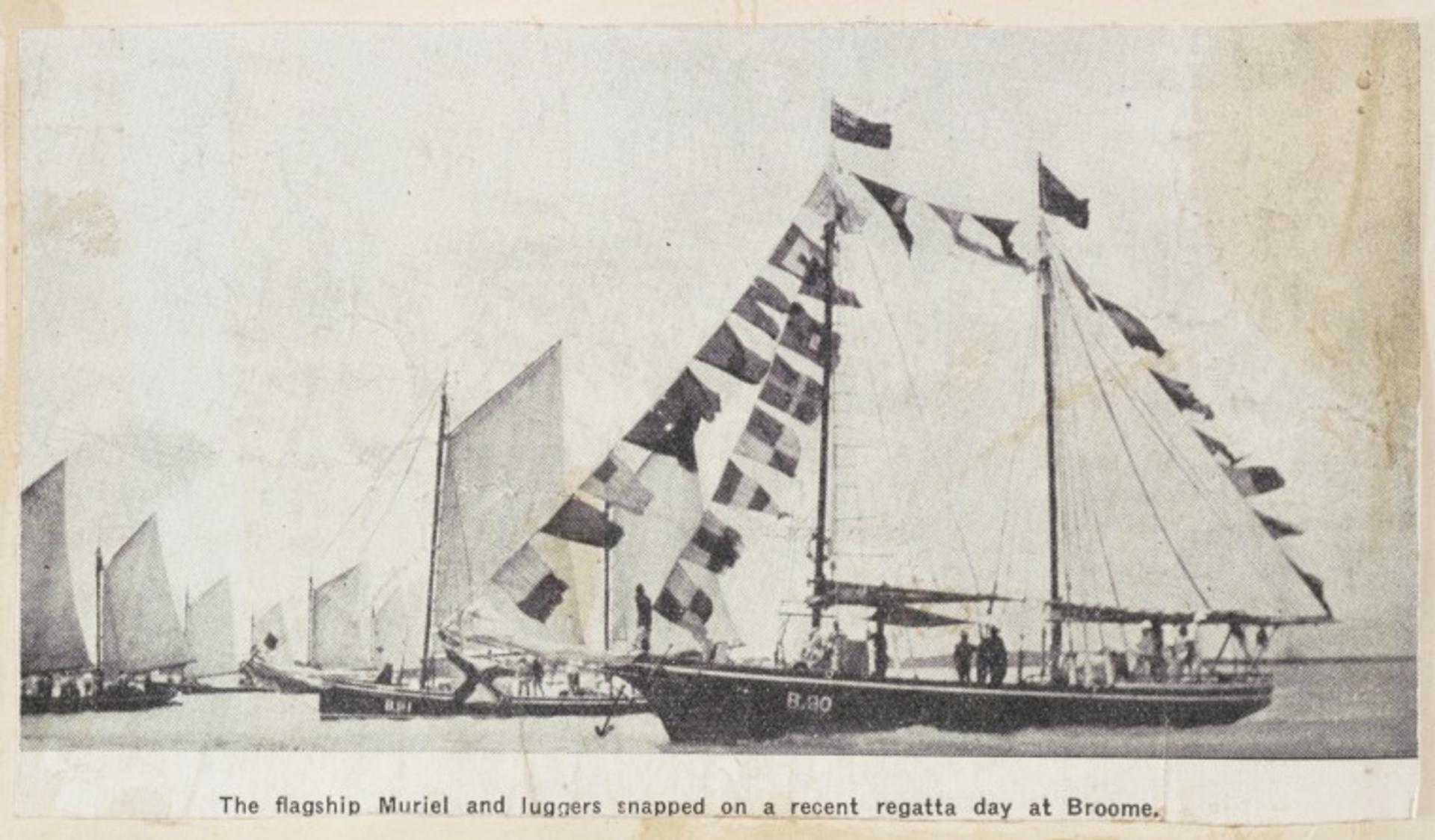

Muriel was a lugger. She does not appear in registered shipping records, so she remains one of the many unregistered luggers working the pearl fields of the northwest of WA. There were multiple vessels of the same name, even in the pearling grounds where so many boats were working.

Muriel was initially owned by pearler, JM Johnson. On 7 December 2012 she became part of his deceased estate. She was sold by tender along with luggers Exchange, Betty, Flores, Eas, Blanche and Arafura. They were bought by Robison and Norman, a successful pearling company in Broome. The contracts of the crews were transferred along with ownership of the luggers.

Each lugger was manned by a crew of 6 Malay men. A typical crew was made up of a diver, tender, pump crew and a cook. One of the crew was likely to be a “try" [trainee] diver. The diver's life depended on the work of their tender. He fed out the lifeline and monitored the air supply. The tender had constant contact with a diver’s lifeline, responding to the tugs on the line that were messages from the diver below. The tender staged the diver’s ascent. A diver’s life depended on his tender. Tenders were often ex-divers or try divers themselves.

Luggers stayed out at the pearl fields for extended periods of time, only returning to shore for spring tides. One of the issues of nighttime anchoring was absence of riding lights across the fleets. The Committee of the Local pearler’s Association in Broome laid down a rule about the necessity of using a riding light for all luggers anchored at night.

A riding light is still required today for boats anchored at night. It is a single white light that is visible from all directions, indicating the boat is at anchor. When a boat has a riding light on, it has no other navigation light visible. On a lugger the riding light was placed on the mast.

One of the loudest voices about luggers who did not use riding lights was the captain of the steam ship Charon. Captain Dalgleish voiced his concerns for the “intense disregard” of the riding light rule. Steam ships were not as reliant on tides as sail boats and were more likely to be moving at night, meeting the expectations of timeframes planned by merchants who were not always familiar with the issues of coastal routes.

The luggers were supplied with oil for the lamps that were used as riding lights. In some cases, the owners did not supply enough oil for the riding light to be lit each night. The oil was also needed for the lights used for shell opening after the diving was done, re-lighting the cooking fire and maintenance work on the pumps and diving equipment. Some crews used their oil for non-work purposes, and did not leave enough to keep their riding light working.

On 26 November 1913, Muriel was anchored with Robison and Norman’s luggers in the large fleet working in 12 fathoms of water 14 miles south of the Ganthaume Lighthouse.

The ss Charon set off from Broome, making for Port Hedland. She sounded her whistle continuously until she was out of sight of Broome, warning boats of her movement in the dark of night.

Muriel had no riding light visible. It was not lit. The crew were asleep. The ss Charon had enough time to build speed in the 14 kms from Broome to where Muriel was anchored. The Charon ran over Muriel, sinking her immediately.

Captain Dalgleish’s worst fears had become reality. He rapidly scrambled his crew to rescue the men from the lugger.

The diver from Muriel was unhurt. One crew member had a fractured skull. Three more men had abrasions and injuries caused by the splintering timbers of the wooden lugger. The tender could not be found after the collision.

Captain Dalgleish made for Port Hedland, arriving at 2.30am. He immediately set about the care of Muriel’s five survivors, and reporting the collision to the authorities.

On 8 December 1913 an investigation was opened, presided by the Chief Harbour Master Captain CJ Irvine. It was discovered that Muriel's owners did not supply her with enough oil to maintain her lights all night. Captain Dalgleish was found to be clear of any fault. The Committee of the local Pearler’s Association impressed the rule for riding lights for to all pearlers in the northwest pearling grounds.

The ss Charon continued with her coastal trade route on the WA coast, adding destinations as far as Darwin and Singapore. She was eventually sold to Yuan Heng Steam Ship Company, who renamed her Yuan Lee. She survived various owners and trading routes until she was broken up for scrap in 1950. She lived a long life for a vessel built in Scotland in 1903.

The crew of the Muriel were indentured men, contracted to Robison and Norman. They were transferred to other luggers to continue their contracts. The name of the lost tender, whose body was not recovered, remains unknown.