Emma

Vessel Name: Emma

Deckhand Grove

Fell overboard; body not recovered

March 1866

All hands and 42 passengers lost

Vessel lost; no bodies recovered

3 March 1867

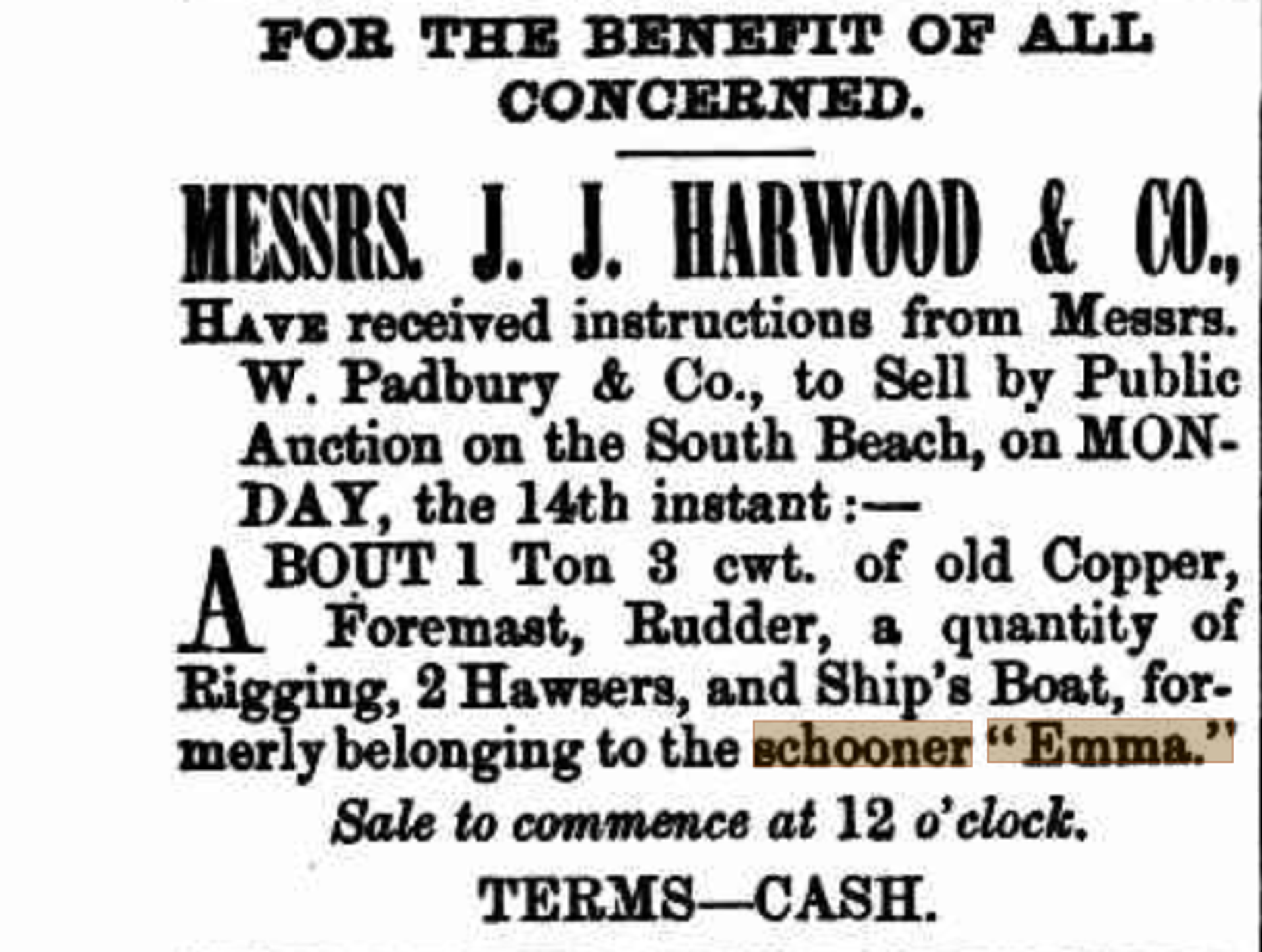

Auction of Emma's fittings

12 July 1867

The two-masted schooner Emma was a coastal tramp, a trading vessel. She voyaged up and down the coast carrying supplies to coastal settlements and taking valuable pearl shell to Fremantle for export. She carried wool south for the pastoralists who were settling arable grazing land along the coast and returned with much needed supplies for farms and settlements along the coast.

Emma was owned by Walter Padbury, who brought her to Western Australia from England in 1866. She was registered in Fremantle as No 1/186. Her official number was 25291. At 116.5 tons, she was 85.6 ft [26m] in length, 20.6 ft [6.28m] across her beam and drew 11.2 ft [3.41m] of water. She was one of the coast's fastest vessels and often broke her own records for sailing from Champion Bay (Geraldton) to Tien Tsin (Cossack).

The schooner went ashore at Champion Bay and struck the jetty before reaching the shore. She was refloated and repaired and put back to work.

One of Emma’s fastest voyages recorded was 4 days and 19 hours from Champion Bay to Spit Point at the DeGrey River mouth on 21 March 1866 under the command of Master C Howard. She had been tasked with carrying 600 sheep and urgent supplies to the settlers who were on short rations awaiting relief. Emma lost only one sheep and off-loaded vital supplies to the government camp which had been several days without food and was affected by disease. When the crew unloaded the hay feed for the sheep, it was discovered that the hay had been wet from watering the sheep. The hay had heated, and a fire had started. It was quickly extinguished before the vessel was damaged.

Due to her speed, Emma was used to transport stock and supplies to the Northwest settlements, with priority given to government funded or subsidised settlements. Despite being a privately owned vessel, she was chartered by the Resident Magistrate to carry urgent supplies where required.

Unfortunately, Emma was what sailors called an “unlucky boat”. She was regularly involved in incidents and accidents like the fire in the hold, and she was often delayed by them.

On an early voyage in her short career Emma made Nickol Bay from Champion Bay in five days. Her return voyage from Nickol Bay to Fremantle took 19 days. Mr Grove was Emma’s mate, and his young son was working on the deck. Deckhand Grove was aloft, hauling a chain that was fast to the try sail. It parted suddenly, causing the inexperienced lad to fall into the sea. The crew saw him fall, and a life buoy was thrown within four minutes, and a boat manned and dropped to the water not long after. The lad was seen to be swimming and then suddenly submerged. He did not resurface. The crew agreed he had been taken by a shark.

On the next voyage Emma lost an anchor, a valuable and necessary item for vessels in the Northwest tides.

On 1 June in her first year, Emma grounded on the Abrolhos Islands on 1 June, on the way north from Champion Bay. The captain and first mate miscalculated their position and changed their course, taking them onto a coral reef. They were forced to put livestock ashore to refloat Emma off the reef. The stock had scab prior to sale and were destined not to survive regardless of the delay. Emma was refloated and sailed to Champion Bay. She was surveyed and cleared to resume her voyage. She made Tien Tsin on 4 July with 491 sheep of the 613 she began with. She delivered urgent supplies to Point Walcott and DeGrey River before returning to Fremantle.

On 30 July 1866 Emma made Fremantle from Point Walcott (Wickham). Then, on 6 August she was one of four boats caught in a storm and beached. While she was being refloated a large wave struck her amidship, causing damage to the hull. She was refloated, but she broke her mooring chains later that same day in another heavy gale, and was thrown up onto the beach again, higher than her initial landing place. Walter Padbury was furious and dismissed the entire crew. There was a considerable delay waiting for tide big enough to refloat her. Newspapers reported she was still beached on 17 August.

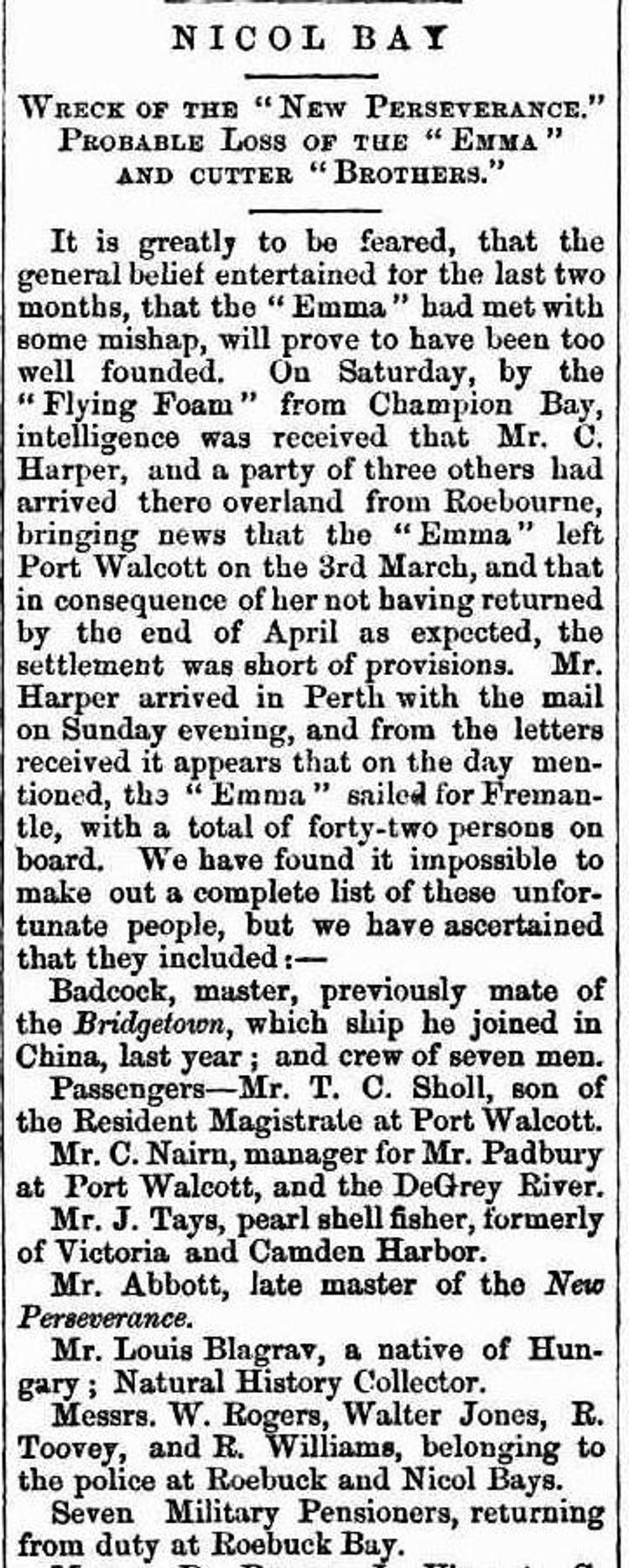

Emma’s final voyage commenced when she was dispatched to the northwest with supplies, and instructions to load several tons of pearl shell and wool from Roebuck Bay Co., Taylor, Knight & Co. and some other graziers on the way back to Fremantle. She left Port Walcott on 3 March 1867. She was never seen again.

Captain Badcock had command of Emma on her final voyage. She had seven crew members and was provisioned for 16 days:

Christensen, the mate

Alexander Clapperton

Alfred Cook

Francis Hamilton

W Hemans

William Johnson

G Cogman

Sadly, she also had 42 passengers, but no list was made to record who was aboard the vessel:

Treverton Charles Sholl, son of the Resident Magistrate, Robert Sholl

Charles Sutton, servant to Resident Magistrate Sholl

Charles Nairn, manager for Walter Padbury, Walcott & DeGrey River Station

William F Tays, pearler, accompanying six tons of his pearl shell

George Grigson

Dan Brown, manager of De Grey Station for Walter Padbury

Louis Blagrav, Hungarian Natural Historian

Captain Abbott of the recently wrecked New Perseverance

Four surviving crew members of the New Perseverance

William Rogers, Roebuck & Nickol Police Officer

Walter Jones, Roebuck & Nickol Police Officer

R Toovey, Roebuck & Nickol Police Officer

Robert Williams, Roebuck & Nickol Police Officer

2 Aboriginal prisoners from Nickol Bay

3 Aboriginal men returning home from service at Roebuck and Nickol Bay

7 military pensioner guards returning home from duty at Roebuck Bay – John Foster, William Purvis, John Byrne, Joseph Barr, Wiliam Whittle, Edwin Radford, John Farrell

J Vincent, government fencing labourer, returning home

G Gregson, government fencing labourer, returning home

Charles Smith, government fencing labourer returning home

Charles Sutton, government fencing labourer returning home

John Staynor/Staines , government fencing labourer returning home

Michael McGrath, government fencing labourer returning home

Breadman, government labourer

White, government labourer

J Fowler, government labourer

J Hogan, blacksmith

A shepherd from DeGrey station

By April, there was concern for Emma, her crew, passengers and her valuable cargo. Brothers was also reported missing, after trying to outrun a cyclone. Had Emma met a similar fate? Her longest voyage was 19 days; she should have made Fremantle before 3 May.

Emma had been a vital link to survival for some of the government settlements on the Northwest coast. The Resident Magistrate Robert Sholl wrote letters to express his concern that she had not returned with provisions to sustain the settlers. By April Sholl wrote to say that the settlers had less than one month of flour left. The settlers at Roebourne had not seen either the Brothers or Emma. By July they were reduced to severe rations awaiting provisions to rescue them from starvation.

As the weeks passed without any sign of Emma, there was heartfelt grief for the families of the crew of the New Perseverance. She was wrecked and sank on 20 December 1866. The crew had been waiting for passage home since then. Some had found work in Roebourne and chose to remain in the Northwest. Captain Abbott and the remainder of his crew had boarded Emma to go home.

By August there was serious discontent from those invested in the fate of Emma. Newspapers wrote asking why there had been no search conducted. Why had no government action been taken over the vessel that linked the south with the northwest?

Finally in July another vessel was sent to Roebourne to rescue the settlers and search for the Emma. On 8 August the Albert was dispatched from Champion Bay to the Abrolhos Islands by the Government Resident, instructing her to search for traces of Emma. Fishing boats had reported seeing lengths of Garden Island timber washed up, and they resembled fittings from the missing schooner.

Emma’s terrible luck continued even after she was lost. Albert was washed onto a coral reef and although undamaged, could not get off without aid. The Water-Police boat sent to accompany her made Champion Bay on 23 August, and assistance was sent to refloat Albert. The results of the search were inconclusive and there was still no clue where Emma had been lost.

Newspapers offered theories as to what may have happened to the missing schooner, but there was no evidence to support anything they published, and there was no sign of survivors. To add to the mystery, Walter Padbury had sold fittings from Emma by auction in January 1867.

There were more than 60 lives lost in commercial vessels in the first two months of 1867.