Ah Chow Sing

Ah Chow Sing

Small hired dingy

Died at Port Denison; body recovered

18 May 1945

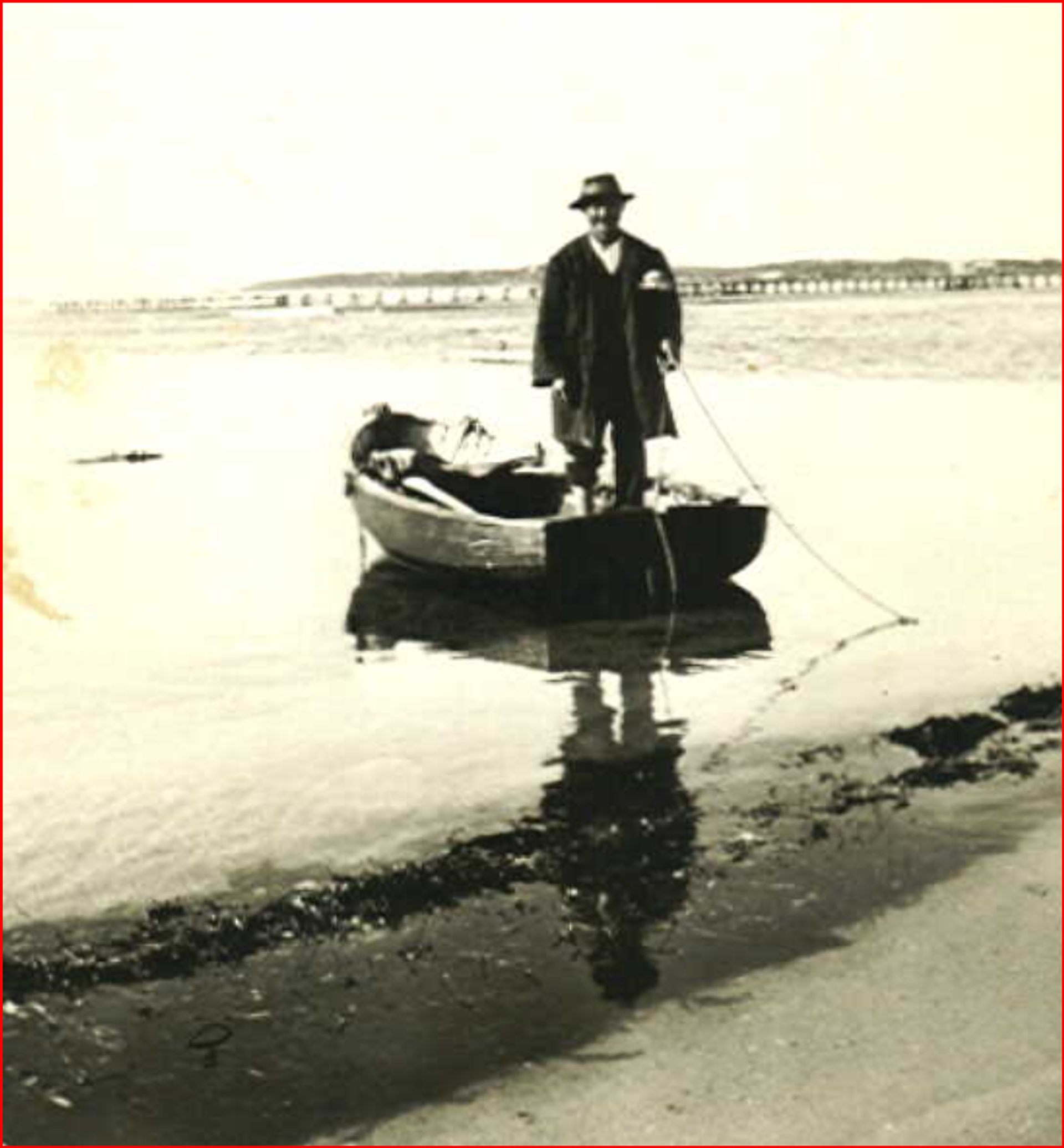

Ah Chow in the dinghy he hired, Photo from the Irwin District Historical Society

Catholic section of Utakarra Cemetery

Ah Chow Sing was born in Melbourne in 1869.He spent most of his life in Dongara, carving out a living, and became an integral part of the small town and fishing communities.

At the young age of 20 years, Ah Chow was called to the Perth Police Court as a witness to a serious assault. Newspapers reported that he requested to be sworn in as a Christian, although he also chose to use the traditional Chinese method with a candle.

There is evidence Ah Chow relocated to Dongara, and he spent the rest of his life in the midwest. His first job, however, was working for Charles Duncan on the Greenough Flats. He soon became well known to the locals there.

On 6 January 1891 Ah Chow was on horseback driving horses to the homestead. They had been out in pasture for some time and were feisty and not best pleased to be driven. Ah Chow rode too close to a bad-tempered animal, who kicked out at him. His left leg was fractured in three places. He was taken to Eaton’s hotel in Geraldton where Doctor Mountain set his leg.

In the weeks it took for Ah Chow to recover, it seems he considered a career change. We next hear of him in Dongara, where he hired a dinghy and fished along the coast, bringing fin fish and cray fish for sale to the public. He paid Jean Leitch each day for hire of the dinghy, declining a longer lease or purchase of a boat himself.

Ah Chow lived in a small shack at Herbert Street, Port Denison. He kept his fishing gear there for netting, potting and line fishing. He sold fish from the front room of the shack and had a room where he mended his nets. In later years the shack became a fish and chip shop.

Ah Chow worked and saved enough to join Ah Pin in a business venture. They bought a boarding house close to the beach. Licensing records indicate they were granted a licence renewal for an Eating and Boarding House on 3 December 1900.Ah Chow seems to have chosen to live simply in his shack.

Having upgraded his residential circumstances, Ah Chow chose to continue fishing with the dinghy and the day-hire arrangement. He sold his catch to locals and visitors and continued to participate in community life.

Dongara was developing with various cultures in its community. There were Sikh families, Chinese gardeners and retailers, and European fishermen joining the small town.

Not everyone was pleased with the multicultural growth of the community. Thomas Hughes and Ah Chow argued over the use of the jetty for fishing. Thomas was the wharfinger (manager of the jetty), and he had the power to stop a person fishing from the jetty. One evening as Ah Chow was riding home on the back of a cart, Thomas ordered him to stop. The cart was driven by the son of the local Money fishing family, who dutifully stopped on command.

Thomas told Ah Chow he could no longer fish from the jetty by order of the Chief Harbour Master on the grounds that he posed a risk of fire because he smoked cigarettes. Ah Chow took offence at Thomas’ attitude and called him a liar. During the heated argument Thomas hit Ah Chow’s arm. A court appearance for both men ensued with both men having claims against the other.

Both claims were dismissed. Thomas was offended his authority was not considered. He claimed that he deserved justice because “any man of spirit” would react in the way he had “if a Chinaman called him a liar”.

Most of the community accepted Ah Chow and appreciated his fish and his congenial personality. He was a hard worker and helped others where he could.

On 17 May 1916 Ah Chow harpooned a large stingray that had been in the bay for some time. He towed it towards the shore. People watching waded out to help him land the stingray, which measured five feet across its width.

On 16 January 1922 there was a small group of children playing in a small flat boat in the shallows. Unfortunately, the boat drifted into deep water, and the children lost the oars, leaving them stranded. Gladys (12) and Percy (9) were strong swimmers. They jumped overboard and swam to shore.

As the boat drifted further, Percy Parker (13) and Sydney Rowland (11) went into the water when the boat capsized in the rougher sea. Sydney was holding his two-year-old brother, and he struggled to tread water and hold his brother high enough to escape drowning. On the shore people watched as he went under the water several times.

Mr Frank Markwell swam out and took the baby and instructed the boys to cling to the dinghy until they could rescue them. George Attrill swam to meet Frank and take the baby when it became apparent Frank was tiring.

Ah Chow watched from the shore. He could not swim. When he saw the boys clinging to the upturned dinghy, he ran along the beach until he found a dinghy. He launched quickly and with practiced strokes, soon rowed out to rescue the boys and bring them to shore.

The rescuers were al mentioned with equal thanks and gratitude in the local newspapers after the event. All the children were deemed to be unharmed by the incident.

Ah Chow was not always on the right side of the law. In 1933 he was fined by Justices of the Peace RW Clarkson, EA Field and CW Dowden for being in possession of an ancient unlicenced revolver. The fine was £1 and 4/- costs. The revolver was confiscated. It was not clear why Ah Chow had the revolver, and the court officials found it hard to understand his explanation in his broken English.

Ah Chow also appeared before the court on two occasions for consigning cray fish which did not fit the regulations set by the Fisheries Department. By 1937 Ah Chow was sending cray fish to the Perth markets for sale there. The Fisheries Department inspected sea food sent to the market, and on 30 January they weighed 98 crayfish sent by Ah Chow. They deemed 54 of them weighed less than the regulation 12 ounces each. Ah Chow was fined £2 and 13/- in costs.

On 17 December 1941 Ah Chow’s catch was inspected by Fisheries Inspector Munroe at the Fremantle markets. The regulations had changed, and crayfish were measured by length. On that occasion Ah Chow had consigned 12 crayfish that were shorter than permitted. Inspector Munroe noted that it was Ah Chow’s second offence, and he was fined £5 with 3/- costs.

Ah Chow fished into his older years, ignoring any idea of retirement. He maintained his daily hire of a dinghy and headed out to the shallows on most days. He was so much a part of the daily hum of Dongara, that despite his age, his sudden death on 17 May 1945 was a shock.

Ah Chow’s body was transported to Geraldton for a postmortem examination on the following day. His death was determined to be from natural causes, likely heart failure. Ah Chow was 76 years of age. He was buried at the Utakarra Cemetery in the Catholic section later that day, 18 May 1945.