Lagalla Family

Country of Origin: Italy

Arrival in W.A.: 1956

W.A. Region Settled: Mid-West

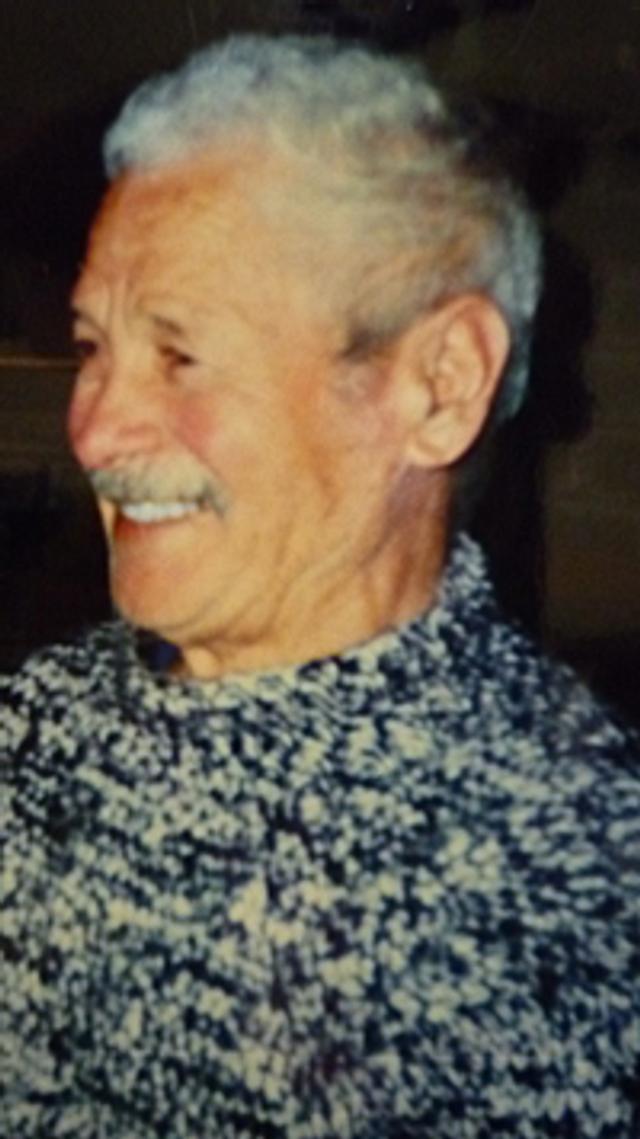

Recently, another legend of the fishing industry died age 98, another pioneer of the fishing industry. Nicola had many experiences worth re-telling, none more memorable than the bravery he showed as a teenager to help the allies in World War II.

Nicola Lagalla

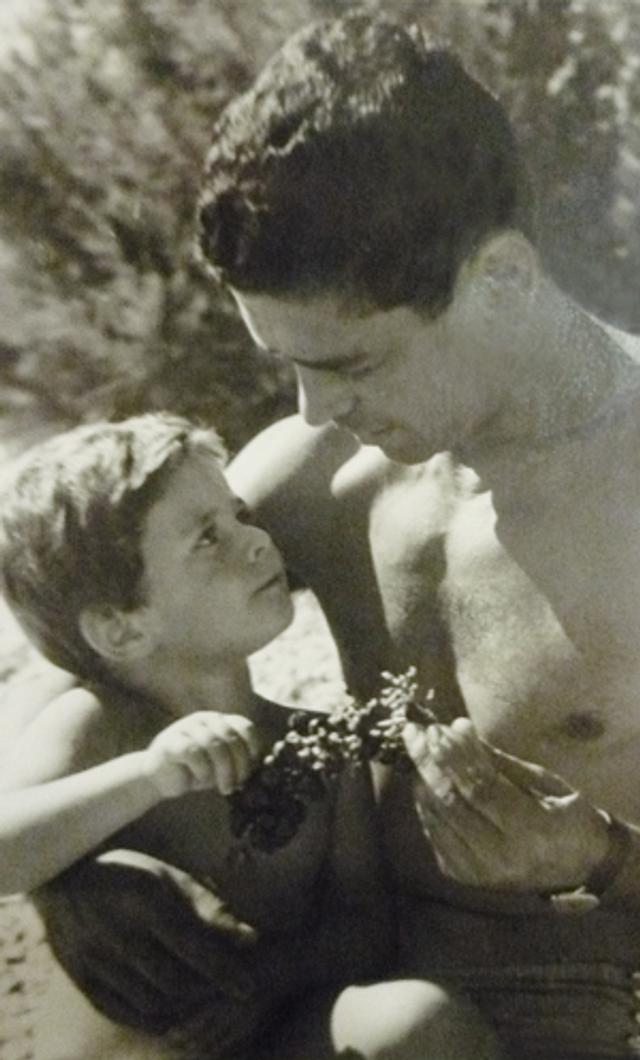

Micola Lagalla and Marida

Emidio and Ida Lagalla

San Benedetto Blessing of the Fleet

During World War II, Nicola and his brother Liberato were instrumental in transporting Captain J. H. Derek Millar and dozens of other escaped prisoners down Italy’s Adriatic coast from San Benedetto del Tronto to Termoli. Nicola’s daughter, Marida, captured the story before and relayed this to Captain Millar’s son, Lenox. At war’s end, Captain Millar assisted in the treatment of the freed inmates of Belsen and Buchenvald concentration camps. After the war, Dr. Millar wrote his MD thesis and became a consultant physician. He and his wife had two children—Lois and Lenox. Following in the footsteps of their father Lois (Millar) Sproat and Lenox Millar both became doctors.

Here is Nicola’s story captured 13 years ago by Marida;

“My brother and I knew nothing of the prisoners until we were approached by Commander Nebbia—my nautical professor—and Mr. Antonio Marchegiani.

“Prior to their approaching us, my brother and I had already decided that we were going to escape [from San Benedetto del Tronto] with our boats within two days. The boats belonged to my nonno [grandfather] Emidio Lagalla.

“They were the only two boats left on the wharf—and due to be sunk by the Germans.

“When Nebbia and Marchegiani came to us, they asked what we were planning to do with the boats. We trusted them and so told them that we had planned to escape with them.

“Nebbia and Marchegiani told us that there were a lot of prisoners waiting to escape. It would be very risky, but would help the prisoners?

“We agreed to take the prisoners on the following conditions: that we had to depart within two days, that all the prisoners had to be hidden at the wharf and they had to be organised, and that the prisoners would not board before we had fully prepared the boats for the escape.

“Our boats were anchored three meters from the jetty. On the day of the escape, it all happened very quickly—the prisoners came on board the boats with dinghies.

“As they came on board, one man was very sick. A soldier with a Sicilian accent told me he was a doctor. If he was the only doctor on board, then he must have been your father. [Nicola is talking to Lenox here about his dad.]

“With the help of another soldier, we took him to the engine room—there were bunks there and the doctor was able to rest.

“My brother and I knew the coast well. When we got to Termoli, everyone disembarked and I did not see your father again.

“The boat that was said to be missing [in Captain Millar’s memoirs], with all the prisoners on board, was the boat that my brother was skippering. It had approximately 60 prisoners on board.

“That boat came into Termoli one and a half hours later. All the prisoners were alive and so happy to be back in safe hands.

“We could not return to San Benedetto as we would have been shot. The Americans took care of us until such time as it was safe for us to return home.”

—Nicola Lagalla

Marida Parkes had this to add regarding her father’s experience:

“I have to say that it is gobsmacking that two kids took those boats. My dad would have been all of 16 or 17 years old and my uncle Liberato about 19 years old.

“Dad tells me my grandfather had no idea that he and Uncle Liberato were going to try and save the boats by escaping San Benedetto del Tronto.

“They were terrible times for all concerned.

“The boats used to assist the POWs were the San Nicola—built by my nonno [grandfather] and named after my dad—and the Luigi Primo. My nonno purchased the second boat, which had already been named.

“Dad and uncle had no money and no diesel for the boats.

“After a while, the Americans supplied them with diesel so that they could take the boats out fishing. They fished off the shores of Termoli, Molfetta, and Barletta. They sold the fish at the fish markets in these towns and then returned to the ship in Termoli.

“There was a curfew at the time—and so, dad and uncle returned to Termoli every day no later than 5 p.m.

“A little twist—in Barletta, dad met a man who had previously been a POW in Tobruk for two years. This fellow was allowed to help dad as a deck hand.

“Whilst out fishing on one particular day, the weather turned very nasty. Dad and the other fellow had to moor at Isola Di Tremiti, which dad tells me was a British Navy Base.

“There, dad was taken by the British, incarcerated, and beaten for four days. The British told dad that a boat called the San Nicola had been dealing with the Germans.

“Dad pleaded his innocence. (I can tell you with absolute certainty that our father would have included some very colourful expletives.) It was to no avail. The beatings continued.

“Dad said the accusations were incredulous, impossible.

“After four days, the British admitted that they had been mistaken.

“Dad was released and taken to hospital so that they could tend to his broken ribs, which were a result of the beatings.

“Hearing my dad tell this story to me today fills me with such sadness. He was 17 years old, only a boy.

“As the Allied forces drove the Germans to retreat, dad was eventually able to return to the port of San Benedetto del Tronto, where he was reunited with all his family.

“I asked papà today, ‘What did nonno say to you when you finally returned with his boats?’

Dad replied, in his usual big voice, ‘MARIDA, WHAT COULD HE SAY?’

“Dad and uncle were awarded a Bronze Medal for Civilian Bravery from Brits.

“Liberato died in San Benedetto approximately 30 years ago from a heart attack. No children. Zio [uncle] was a gorgeous man, with his huge, black horn-rimmed spectacles. He was a very calm and gentle man. After the war, Liberato did not pursue his fishing career. He became a glazier.

“I don’t think dad quite understands how he and uncle may have been instrumental in changing outcomes. I am not saying here that they were heroes. But I am acknowledging dad’s humanity, and also that of my uncle, and that of so many people who have been willing to risk everything to reach out, to help their fellowman.”

“Dad married Maria Bartolomei—they lived next door to each other in San Benedetto Del Tronto, so she was ‘the girl next door.’ They had four children. I was the first, then Robert, Paul, and Sabrina. Dad, mum, and I immigrated to Australia in 1956.

“Dad eventually became a licensed crayfisherman, and in a short period of time purchased his own boat. Initially he had the Maria Laura, and later the Kon Tiki—it went one-mile forwards and two miles backwards it was so old. But as they say in Lancelin—’he killed the pig’.

“His catches during a couple crayfishing seasons, as well as working in the prawning season in the Exmouth Gulf, had set dad up for life. He built a new boat with all the latest equipment on it and has not looked back since.

“My dad was such a worker, and still he pushes on. He has a few ailments, but for his age he is incredible. He is funny, generous, tenacious, and headstrong. He is still fishing on his mini crayfishing boat at age 85.

“In all, he is a terrific papa.”

Story Contributors

James Paratore

Marida Parkes